Well, almost. Though discovered in 1988, gamma Cephei A b was officially confirmed as the first discovered exoplanet years later, in 2002. At the time, the search for exoplanets was not a research priority area, and techniques to do so were still in need of much refinement.

To track the motion of stars as a way to detect exoplanets, the research team, composed of Gordon Walker, Bruce Campbell and Stephenson Yang, had come up with a new detection method called radial velocity. By tracking stellar wobble, they aimed to determine if the star was hosting a planet. From their detailed measurements, they'd seen that gamma Cephei had a periodic 2.5-year-long wobble. But at the time, the amount of perceived wobble made it difficult to determine if the wobble was caused by the gravitational forces of an orbiting planet, or if the wobble was just caused by regular star activity. Then came the discovery of 51 Pegasi b, announced in 1995, by Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz from the Geneva observatory.

To this day, exoplanet hunters still disagree over who made the first discovery, as both American and European teams claim to have been first. Today, the radial velocity method for exoplanet detection has been replaced by a more precise method: the transit method.

Since the 1980’s, detection methods have evolved. Years later, space missions such as Kepler established that extrasolar planets were abundant. There are some 100 to 400 billion stars in our galaxy and there may be as many, or more, planets orbiting those distant stars! There may also be many rogue planets - planets that are free-floating, not connected to a star - yet to be discovered. An upcoming NASA mission, the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, should be able to find hundreds or more of these rogue planets.

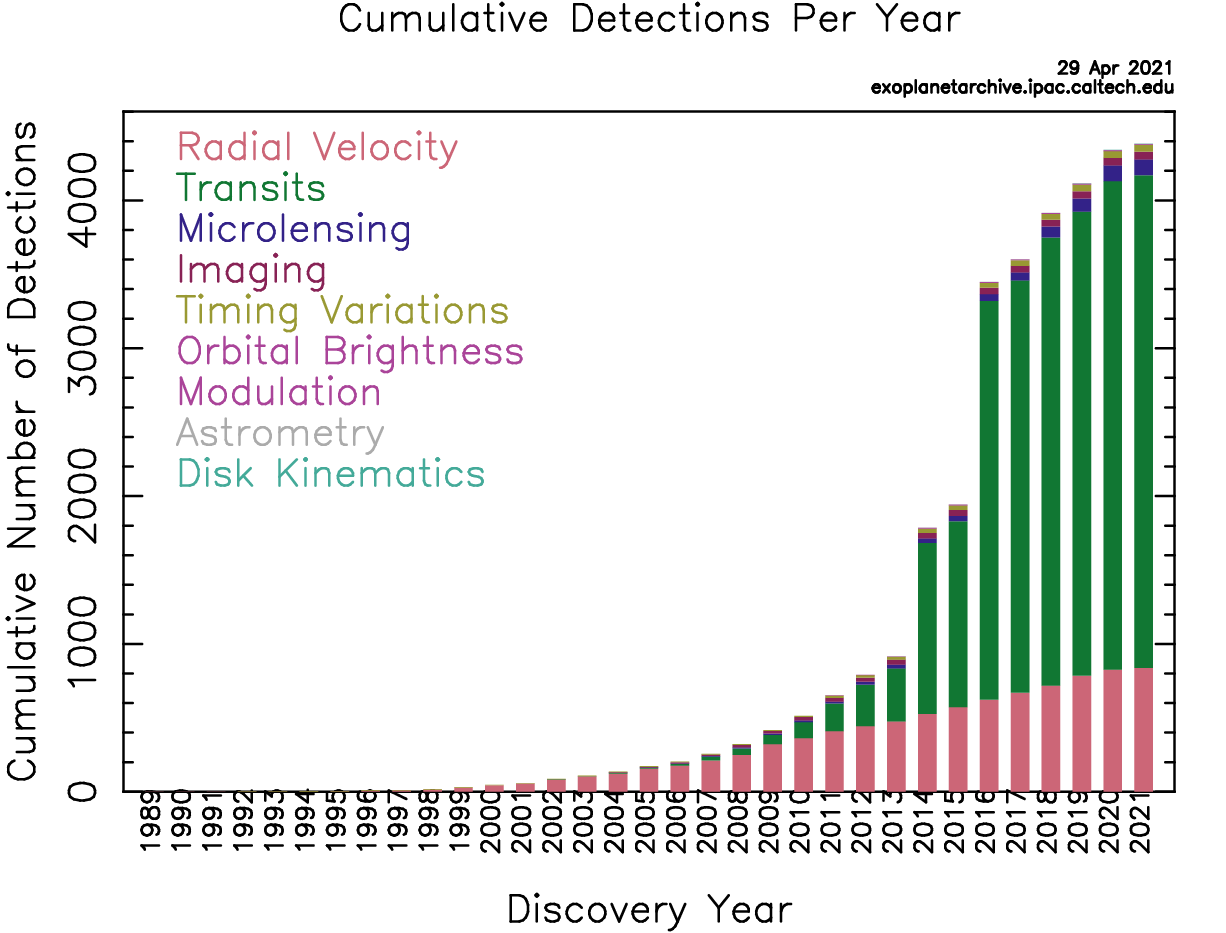

The number of confirmed exoplanets has been exploding since 2016, with the last three years of confirmations bringing in the greatest hauls.

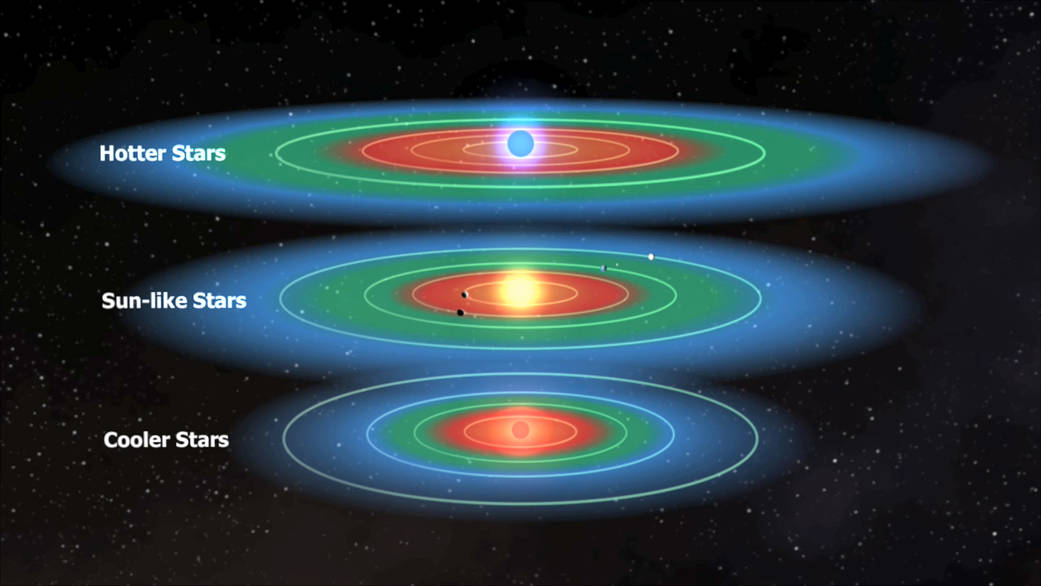

The Earth's primary source of energy is light from the Sun. If the Earth were to be much closer to the Sun, then the amount of energy received would increase drastically, making our world inhabitable. Likewise, if the Earth were much further away from the Sun, then our atmosphere would freeze out. The distance range at which the Earth can maintain its atmospheric properties and allow liquid water to exist is known as the habitable zone. The position and width of the habitable zone is dependent on the properties of the host star and the planet.

We learned that low-mass stars are intrinsically faint. They emit less than 10% the light of the Sun. For an Earth-like planet to be habitable around a low-mass star it must be situated much closer to it's host star.

In this image, you can see the relationship between the temperature of the star and the size and location of the habitable zone (shown in green). The habitable zone around hotter stars is wider and exists far away from the star, while for cooler stars the habitable zone is narrower and closer.

Remember the TRAPPIST-1 system discovery, back in 2017?

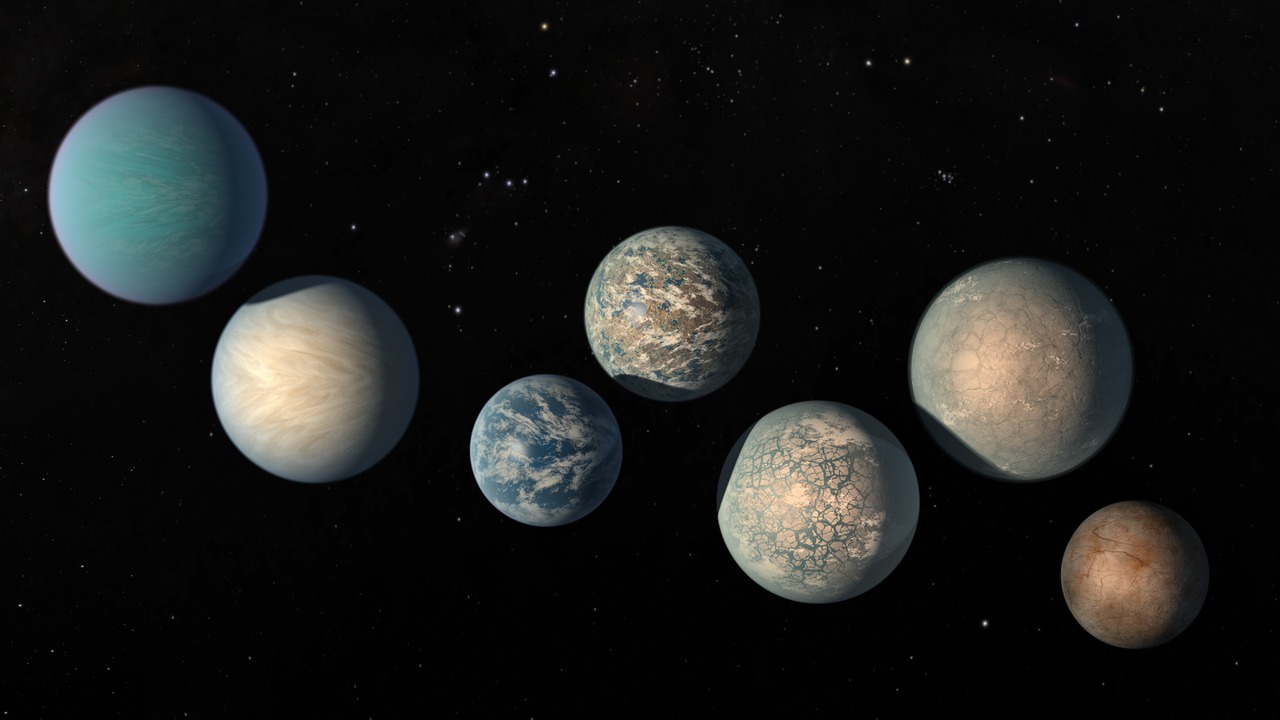

TRAPPIST-1 is an ultra-cool red dwarf - a protostar larger than a brown dwarf - which is much cooler than our Sun. Its planetary system consists of at least seven rocky planets, the most numerous detected so far

This system has the particularity of being very compact, as all its planets are located on an orbit smaller than that of Mercury! Three to six of the discovered planets are located in the habitable zone. TRAPPIST-1 is the best target yet for studying the atmospheres of potentially habitable, Earth-size worlds.

The illustration above shows the seven Earth-size planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1. The image does not show the planets' orbits to scale, but it shows a wide range of how these planets might actually appear!

The discovery of the TRAPPIST-1 system gives us a good idea of how habitable zone planets orbiting around cooler stars can be detected, and how our microsatellite will be aiming to do so.